REMEMBRANCES: America in 1962, when the world almost ended

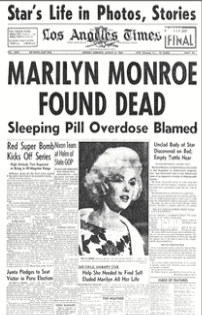

Like every year, 1962 had its moments of joy and sadness. It was hilarious to witness a sultry Marilyn Monroe sing “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” to John F. Kennedy in May, and devastating when, sadly disturbed, she died of a drug overdose three months later. It was grimly satisfying to see Adolf Eichmann hanged in Israel for his monstrous crimes against humanity, and it was surprising to see Pat Brown defeat former presidential candidate Richard Nixon in the race for governor of California, seemingly ending the latter’s political career.

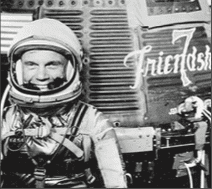

We all cheered 60 years ago when John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth and when Telstar was launched in July, becoming the world’s first communications satellite. In the entertainment field, we saw Johnny Carson become the host of the Tonight Show – a gig that would last for 30 years – and we heard the first hit song of 20-year-old Bob Dylan, “Blowin’ in the Wind.” But nothing dominated our news and our lives like the 35-day period from October 16 to November 20, known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

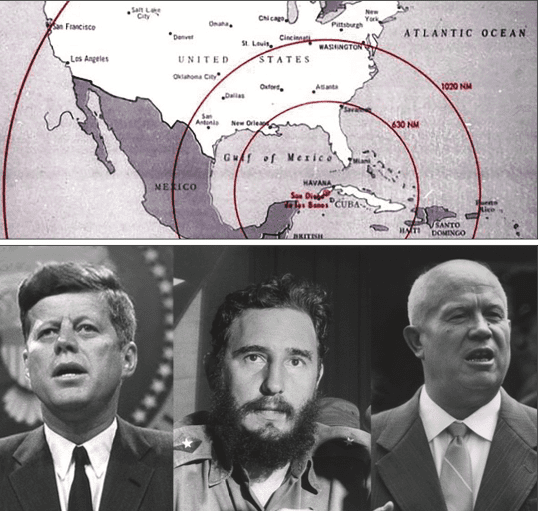

In April a year earlier, a U.S.-backed group of Cuban exiles had been defeated at the Bay of Pigs in an abortive attempt to overthrow the Communist Cuban government run by Fidel Castro. An exasperated Castro decided to retaliate by allowing the Soviet Union to place some missiles in his country to deter any further incursions by the United States.

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev relished the opportunity. First of all, he knew that the U.S. held a big advantage in ICBM numbers (the so-called “missile gap” was actually in our favor), and he could level the playing field by putting Soviet medium-range missiles close to U.S. borders. Secondly, he was unhappy with the recent placement of U.S. Jupiter missiles in Turkey, close to his own borders. This would be tit-for-tat. But Khrushchev’s real objective was West Berlin, then under the protection of the U.S., Great Britain and France. He felt he could gain control of this prize by threatening a missile attack from Cuba if the Western powers resisted his moves against the one-time German capital – or by offering the Cuban missiles as bargaining chips: the Cuban missiles for West Berlin.

Khrushchev and his advisors judged JFK to be weak and indecisive. After all, in just the past year Kennedy had kowtowed to Russian moves in building the Berlin Wall and had botched the Bay of Pigs invasion. He would be too preoccupied with midterm elections to take action elsewhere. So it was that by mid-September, nine separate missile launch sites suitable for medium-range ballistic missiles armed with nuclear warheads were being rushed to completion in Cuba. Once they were completed and armed, the U.S. would have to accept a fait accompli.

In the U.S., rumors were spreading that the Soviets were doing something in that island nation just 90 miles from our shores. But what? We had been sending U.S. Air Force U-2 spy planes over Cuba since the end of the failed Bay of Pigs mission, but the flights had been halted on September 10 due to highly publicized U-2 incidents elsewhere around the globe. When ground-based intelligence pointed to offensive missile sites, the overflights were reinstated on October 9, and on October 14, photographic evidence was gathered that the Soviets were indeed constructing medium-range and intermediate-range ballistic missile launchers there. After verification by CIA specialists on October 15, the President was notified of their findings on October 16.

For Kennedy that was a game changer, a major escalation of the Cold War. It would reduce our nation’s response time to a Soviet missile attack from minutes to seconds. Moreover, it would for the first time place a Soviet military presence in the Western Hemisphere, where Khrushchev could sow discord in the often volatile affairs of our Latin American neighbors and perhaps create military alliances to our detriment. President Kennedy had to act, and act quickly.

He did, calling together that evening a group of top advisors that became known as EXCOMM, to determine a course of action. The EXCOMM team included Kennedy’s brother Robert, at that time the Attorney General and JFK’s closest and most trusted advisor. Also aboard were Vice President Lyndon Johnson, the Cabinet Secretaries of State (Dean Rusk), Defense (Robert McNamara) and Treasury (C. Douglas Dillon), the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (General Maxwell Taylor), National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy and several key executives from the Central Intelligence Agency. Rusk initiated contact with the 21 members of the Organization of American States (OAS) at that time, alerting them that a crisis was developing that could lead to war.

On that same day Robert Kennedy called in Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, who assured him that the Soviet Union was bringing in only defensive weapons and had no intention of disrupting the USSR’s relationship with the U.S. But EXCOMM was not buying that. In their evening meeting they discussed their options: applying diplomatic pressure on the Soviets to remove their weapons, executing an airstrike on the missile sites, setting up a naval blockade of the island to prevent the delivery of any more missiles, or undertaking a full-scale invasion of Cuba.

The option for merely diplomatic action was correctly deemed to be too weak. The Joint Chiefs of Staff were unanimous in wanting a full-scale invasion, but JFK demurred. That was an act of war, and the Soviets would have to respond, either militarily in the Caribbean or by moving on West Berlin. On October 18 President Kennedy met with Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, who reiterated the Soviet claim that only defensive weapons were being sent to Cuba. Kennedy knew better, but he did not let on what he knew, and the next day new photographs came in showing that four sites were now operational.

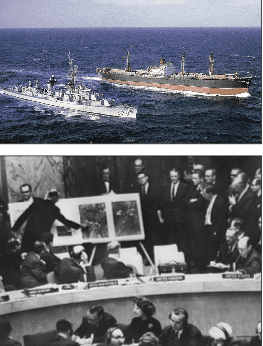

For the next two days of continuous meetings, EXCOMM looked at alternatives to invasion – either an airstrike or a naval blockade. Sentiment built in favor of a blockade, but there was a drawback: Under international law, a full blockade was considered a declaration of war, and the already serious confrontation might explode into combat by the world’s two giant nuclear powers. After consultation with our OAS partners, it was concluded that using the term “quarantine” would limit the scope of the naval action to prohibiting offensive weapons. That would get around the legal issues associated with the term “blockade.”

After lengthy conversations with our NATO and OAS allies received their endorsement of our action, President Kennedy went public on October 22 in a televised speech to his countrymen. The United Press International, Inc. reported on his statement, which said in part:

“It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union. To halt this offensive buildup, a strict quarantine on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba is being initiated. All ships of any kind bound for Cuba, from whatever nation or port, will, if found to contain cargoes of offensive weapons, be turned back. This quarantine will be extended, if needed, to other types of cargo and carriers. We are not at this time, however, denying the necessities of life as the Soviets attempted to do in their Berlin blockade of 1948.”

The nation waited breathlessly. Would the Russian ships turn back? In an exchange of telegrams over the next two days, Kennedy and Khrushchev sparred over the issue, and the Soviet leader threatened to order his ships to ignore any blockade.

When on October 25, in an emergency meeting of the U.N. Security Council, the U.S. called for the USSR to admit it was sending offensive missiles to Cuba, the Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin refused to do so. That did it. The next day Kennedy ordered that the U.S. Strategic Air Command be placed on DEFCON 2 readiness. B-52 and B-47 bombers armed with nuclear weapons were put on continuous airborne alert and dispersed to strategic locations around the globe. Our ICBM missile silos stood ready to attack prearranged targets in the Soviet Union. The U.S. Military Air Transport Service commandeered just about every available plane (including many commercial aircraft) for shipping supplies and troops to Florida,* and U.S. naval vessels were placed on high alert in the Caribbean. All of these measures were deliberately undertaken openly, so that Khrushchev would see that JFK meant business this time.

He did. Khrushchev decided to look for a political solution to the crisis and eventually found one. The U.S. would agree not to invade Cuba and would remove the Jupiters in Turkey. The Soviets would remove the missiles from Cuba and destroy the launch sites. Despite almost solid opposition from his senior advisers, Kennedy quickly embraced the Soviet offer. It gave Khrushchev a face-saving way out of the situation – and after all, there were only 15 missiles in Turkey, which were already outdated and would in any event soon be replaced by submarine-launched missiles. The deal was sealed, and on November 20, the crisis was officially over.

An important outcome of the crisis was improved communication between the two world leaders. Messages between them had taken up to 12 hours to decode and translate – far too long in a fast-moving scenario. On June 20 1963 the United States and the USSR established the Direct Communication Line, better known as the hotline that is still in service today.

President Kennedy had been told in early 1961 that a nuclear war would likely kill a third of humanity. In those critical 35 days of the Cuban Missile Crisis, we were teetering on the edge of a nuclear face-off, more than once within minutes of making war. A misjudgment or mistake by a political leader or an on-duty military officer could have led to disaster. Between them, the two countries had about 30,000 nuclear weapons, with an explosive yield equivalent to approximately 6.3 billion tons of TNT. That might have been sufficient to trigger a runaway greenhouse effect in Earth’s atmosphere, leaving the planet like its twin sister Venus, whose surface temperature is close to 900 degrees Fahrenheit. At the very least, the world that we knew would have ended.

_____

*I can personally vouch for this. I was among a group of 16 scientists and educators who had been invited to visit the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama at that time to meet Wernher von Braun, the head of our space program, and observe a static firing of the Saturn rocket. We were delayed for several hours at McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey until a plane could be found – a rattletrap C-47 with metal seats, and we rode with parachutes strapped to our backs. After a bumpy, smoke-filled six-hour flight we did get to meet Dr. von Braun, but the Saturn firing was scratched.