Environmental and manmade problems plaguing local seagrass leave manatees and other aquatic wildlife in dire straits

After a massive hurricane and a year of drought, the status of seagrass in Charlotte Harbor could perhaps be characterized by experts as “not better, in fact marginally worse.”

“We have lost massive amounts of seagrass,” said Dr. Richard Whitman, who heads up the nonprofit environmental charity Heal our Harbor. The group looks regularly at the water quality in Charlotte Harbor and its tributaries, enlisting volunteers in monitoring and educating about the importance of our water.

Observations are often anecdotal and micro-observations, and not all seagrass is the same. Whitman likens the question to how the stock market is doing. Are you asking about how it is doing this week, this year or over decades?

The bad news is that Hurricane Ian not only put a wall of nutrient plumes into the water and out into the Gulf of Mexico, but the giant movement of the water itself from the storm stirred up the sea-bottom mess that was there already.

Seagrass is affected by water temperature, nutrient availability, salinity, sediment type and light. Each has an effect, but the light is always an issue.

The question about seagrass is the type of grass, and what forms of wildlife are growing in it.

“We can’t always say cause and effect,” said Whitman, who is the former manager of the Lake Michigan Ecological Research Station and also was a chief scientist for the National Parks Service.

Nicole Iadevaia, the director of research and restoration for the Coastal and Heartland National Estuary Partnership (CHNEP), said that Charlotte Harbor has seen seagrass losses since 2018, including Hurricane Irma and followed up by red tides, then Ian. While she thinks the system can bounce back, it’s taking a lot of hits.

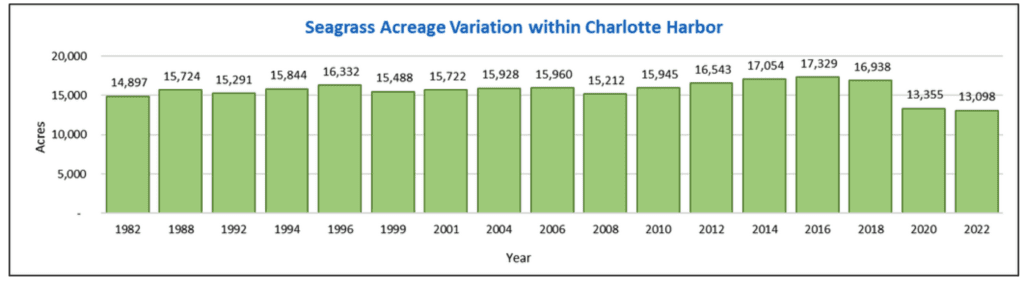

The latest statistics from CHNEP and state sources showed 13,098 acres of seagrass in Charlotte Harbor in early 2022, down from a high of 17,329 in 2016. From 1982 on, there had been a steady increase in the number of acres, but those gains have been lost. That 2022 figure did not include damage from Ian.

She said that unlike other areas in the state, Charlotte Harbor had always been a lush estuary that never saw the habitat destruction seen in highly urbanized places like Tampa Bay.

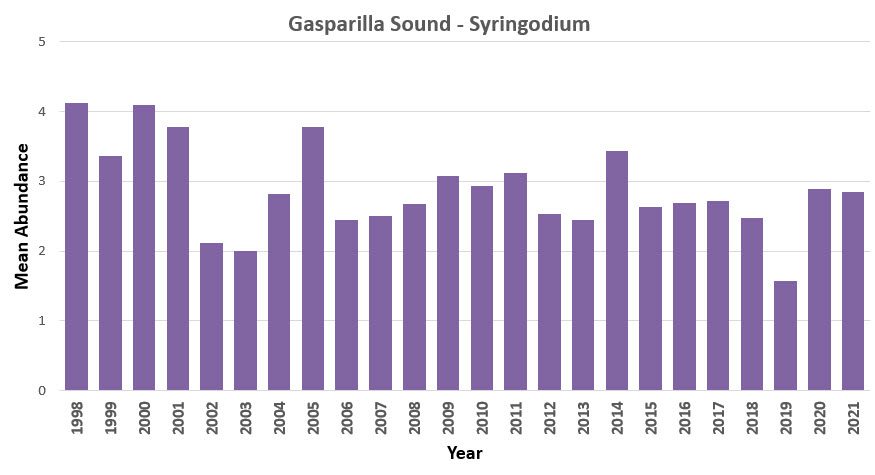

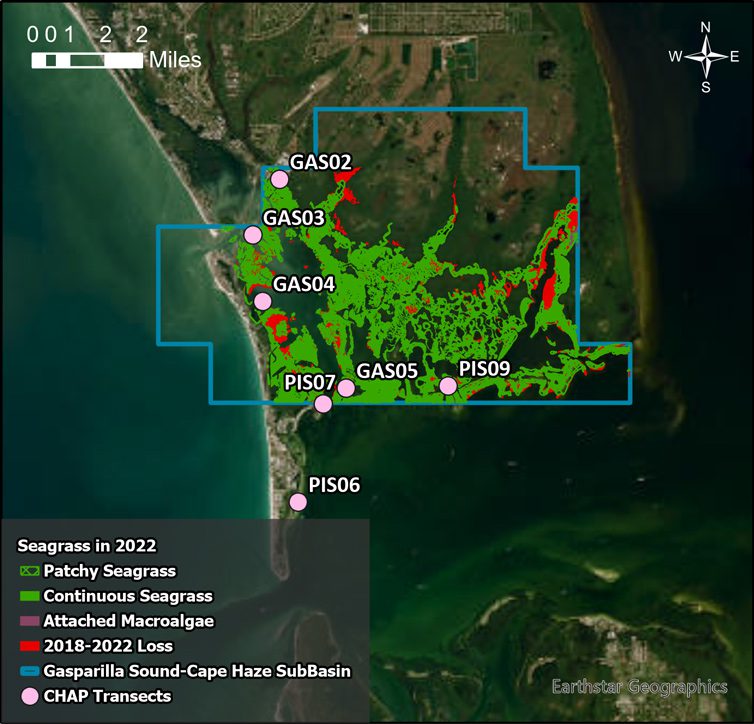

Looking at particular grasses, Iadevaia said that essential turtle grass, dominant in the southern part of Charlotte Harbor, had experienced losses and only partial regrowth. But in the Cape Haze area, shoal grass, which “comes and goes,” had seen an increase.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s Office of Resilience and Coastal Protection manages the Charlotte Harbor Aquatic Preserves. They referred all questions to the state Department of Environmental Protection, which did not reply to a request for comment by press time.

Underwater Salad Bar

Carter Henne is co-founder and president of Sea & Shoreline, a Florida seagrass and aquatic restoration firm that worked on the Mercabo project. Their claim to fame is to have planted more seagrass than any company in the world.

“If there is not enough salad in the salad bowl, manatees, turtles, ducks, snails, fish, urchins – you name it – everything gets reduced to nothing,” Henne said.

Henne also believes we should not let the changes from the hurricane dissuade us from the progress that has been seen.

The drought this year has helped the water avoid major algae blooms, albeit temporarily. This is good news, Henne said. As an overarching trend, there have been a lot more nutrients in the system than has traditionally been the case.

Seagrass as a whole holds the ground down and stabilizes the sediment underwater, acting like a carpet that keeps sand from moving around. Henne calls seagrass a “self-perpetuating story, until something happens.”

Long-Term Improvement

The Atlantic side, Indian River Lagoon for instance, has had a small recovery of late, Henne said.

The story along the Gulf of Mexico in Florida is a generally improving story over the past few decades that has won international plaudits. Tampa Bay, for instance, spent millions to reduce nutrient load in the water to get water quality back to where the area was around 1940. The region mostly met that goal.

These successes have spurred public support for other highly visible and politically popular solutions, such as the pyramid-shaped Wave Attenuation Devices, or WADs at the Sunshine Skyway. Anyone driving along the Skyway in the last few months has seen these giant concrete triangles that are there to stabilize sediment and to encourage grasses.

Crystal River, a critical manatee area north of Homassassa Springs, has also been a community-led success, taking a famous manatee habitat from about an acre of seagrass to almost 300 acres. This came after the area had exhausted other expensive options, including completing expensive septic-to-sewer conversions.

“They did everything they could,” said Henne. “The manatees were ripping out the plants, but it wasn’t their fault. The ground was too soft. So we figured out that by vacuuming and removing all the muck from the bottom, we could get down to a hard substrate. Then, when the manatees came to eat the plant, the leaves broke off but the roots stayed there. And then they simply put out more leaves.”

The first year, they didn’t even get a plant over an inch tall. The second year they planted more acres and had plants about two feet tall.

“At the end of the third, year, we found our first seed,” said Henne. “Seed pods coming up all the way to the surface. And then it started taking off exponentially.”

Simple Solutions

In terms of what the average person can do easily to improve the situation, locals can consider what they do while boating and what they do with their lawns.

Charlotte Harbor is notoriously shallow, for instance, and boaters run aground frequently. Henne said that by trimming up your motor and pushing yourself off seagrass flats instead of doubling down on the horsepower, you can help to preserve them.

Boaters can deteriorate a seagrass flat so much that it cannot function on its own and stabilize sediments.

“Individually, it’s not a big deal,” said Henne. “But when you have as many boaters as we have in the state now, it adds up.”

Iadevaia said a map of propeller scars in Charlotte Harbor since the 1990s showed a “crazy” amount of destruction.

At Mercabo (located at the entrance to the Gasparilla Island Causeway), the company built a seagrass shelf with nursery-grown stock. Shoal grass taken from a nursery can make way for more dominant species like turtle grass to fill in and grow the ground around it.

Teaching citizens is part of the solution. Protecting our waters is partly education and training. This week, Whitman happened to be reaching out to property owner associations, to encourage crews to not let the grass sprayed from lawnmowers get into the canals. “Sometimes it’s just not good supervision,” said Whitman.

Local Seagrass Priorities

Seagrass is still an underappreciated system in the Gulf of Mexico, according to Dr. Jennifer McHenry of the Department of Biology at the University of Victoria, British Columbia. She and local co-authors Andrew Rassweiler and Sarah E. Lester just published a paper in the journal “Ecosystem Services” that details why the benefits from seagrass are different according to their location. In some areas they help protect shorelines. In others, they support commercial and recreationally harvested species.

Charlotte Harbor, she said in an email to the Boca Beacon, happens to be “one of a handful of locations on the Florida Gulf where seagrass provides a very large number of important benefits.”

She explained that when we lose seagrass beds here – from poor water quality to climate change – we have much to lose. In restoration, we need to consider community needs, costs and future risks.

“At the same time,” she said, “it also means that focusing management and restoration efforts in these places could lead to the greatest return on investment, in terms of the outcomes for seagrass ecosystems and coastal communities.”

Henne summed it up succinctly.

“There is not one thing that makes seagrass go away, and there is not just one thing that makes it come back.”