Mote Marine tests shark-repellent devices

Electromagnetic technology could reduce fishing depredation

Scientists at Mote Marine Laboratory’s research facility in Sarasota are testing devices that send electric pulses intended to repel sharks from caught fish.

Demian Chapman, senior scientist and director for Mote’s Center for Shark Research is leading shark research at the Marine Experimental Research Facility (MERF). Currently at the facility, they have two adult sandbar sharks in a 60,000-gallon tank and many baby sandbar sharks in a smaller 40,000-gallon tank, Chapman said. They are testing these repellent devices on the two adult sharks.

“Sharks, they’re sensitive to very minute electric fields,” Chapman said. “So, a lot of times, if you look at the underside of a shark snout, it looks like they have blackheads … basically, those are little electrosensory pores. So, all living things emit these tiny, little electric fields just because our nerves are firing, our heart is beating and all this stuff. It’s almost like you have this little aura. And we can’t sense that, but sharks have the ability to sense these little electric fields, and they use that to find prey, like when it’s hidden in the sand, for example.”

These repellent devices take advantage of sharks’ electrosensory pores to deter them temporarily.

“In nature,” Chapman explained, “there are certain animals that can shock you, like electric rays, for example. A colleague of mine just showed that the torpedo rays, they’ll actually shoot off an electric charge when they’re being attacked by a shark, and it repels the shark. So that’s more or less what we’re trying to do with these devices.

The idea is that you either put the device on your fishing gear, right by where the fish will be when it’s hooked, you clip it to the line and slide it down, and it reaches the fish. It’s a device that’s manufactured by a company called Fish Tech, and basically it emits every second this electrical pulse that’s higher than what the shark would normally experience. It’s not as much as the torpedo ray would hit them with, but it’s enough that they don’t like it.”

These devices are fairly new on the market, and not commercially available yet; however, if an angler were to attach one to their gear, the idea is that once a fish is caught and a shark approaches to take the fish, the shark would experience an over-stimulation of its electroreceptors and turn away, giving the fisherman time to reel in the catch.

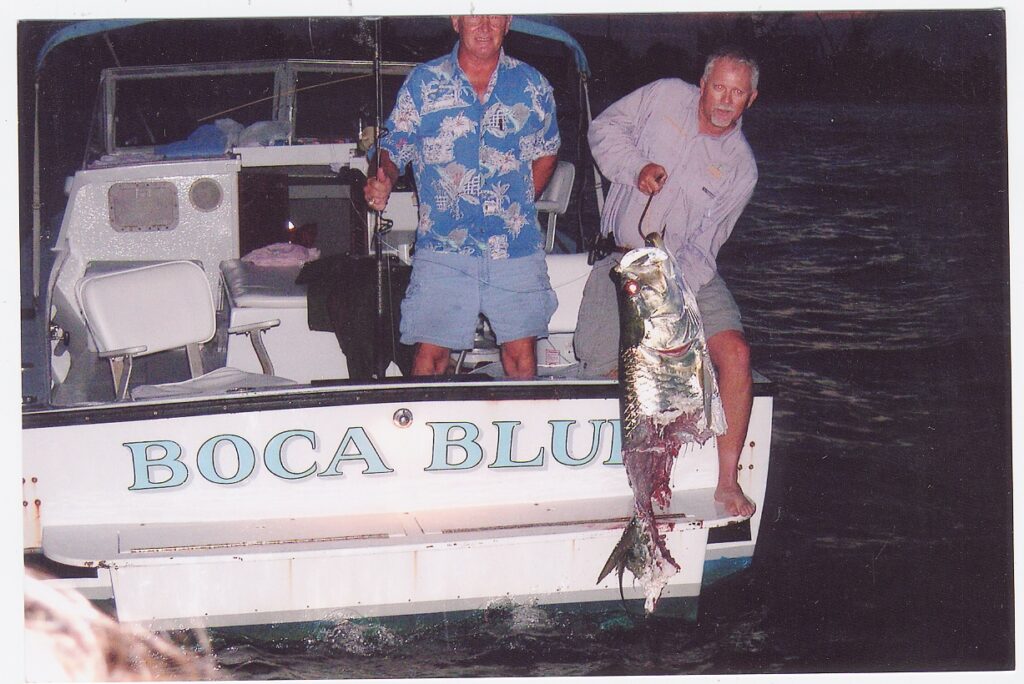

This depredation behavior, in which a shark partially or completely removes a hooked fish from a line, is a growing concern for anglers, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries. An increase in shark depredation could be attributed to more sharks, more anglers or even learned behavior.

“Some evidence suggests sharks can learn from previous interactions and begin to associate the sounds of fishing boats with easy meals,” according to NOAA.

Mote is not manufacturing repellent devices, but is objectively testing them on temporarily housed sharks.

“Any company that has a device like this, we will test it, because obviously we have the ability to keep sharks, expose them to it,” Chapman said. “What we do is we turn it on and we turn it off. We’ll give it one try with it off, another try with it on and keep moving back and forth like that. Because our goal is to see, does it actually work? And what we’re typically finding is, yes it does. Typically, it delays how long it takes the shark to get a food item. And the reason is, because they’re coming in, and a lot of times they experience that little shock and they take a detour.”

“There are similar devices that divers and surfers use, such as SharkBanz, especially in Australia,” Chapman added. “I do think this is something that fishers will start to get behind,” he said. “We want to give the manufacturer any feedback so that they could make it better, and we also want to make sure that anyone trying to use it knows when it works and when it doesn’t. It’s not a magic bullet that’s going to stop a hundred percent of sharks taking fish, but it might reduce it by some decent percentage that makes it worthwhile.”

This depredation is mainly a problem off Gasparilla Island during tarpon season in May and June.

“The tarpon are coming through on a migration, and sharks are very keyed in to feeding opportunities,” Chapman said. “And so, in some cases, they might be following the tarpon the whole way. Or these sharks might be in a different location, and they just know the tarpon are here at this time and concentrated so they’ll all come in.”

This past June, in the middle of tarpon season, a nine-year old girl was injured by a shark, only the third reported shark bite since 2005.

Mote has been doing surveys of large sharks since 2003, going out every quarter to essentially measure sharks-per-hour.

“There has been an increase from the early 2000s until now, but it’s a mild swelling,” Chapman said. “It’s not a huge change. Statistically, yes, there has been an increase, but there’s also been a large increase in the number of people using the water. So, if you have a slight increase in the amount of sharks but a large increase in the amount of people, that’s how you get more of these sorts of interactions between fish, and sharks and bathers.”

Florida had a total of 14 unprovoked shark bites in 2024, the majority of which were on the East Coast of the state according to data from the Florida Museum of Natural History’s International Shark Attack File.

“There’s definitely shark bites that happen in the Gulf,” Chapman said. “It’s such a rare thing that, if you have three or four in one year, and you have one in the year prior, on the one hand, you could say it’s triple the amount, but it’s also only three. So, you can have that kind of swing that makes it seem like there’s a lot more. Shark bites on humans are sort of like this statistical impossibility to deal with. Because they are so rare, it’s hard to really say what’s the trend. And the thing I always like to keep in mind is that you have no idea on any given sunny day how many people are swimming in the Gulf, but if sharks wanted to take us as prey, it would be a massacre … so we know they’re not going after people. That’s the only thing we do know.”

Chapman recommends being cognizant of where tarpon are during May and June, and using common sense.

“If you’re out swimming and there’s a whole bunch of fish around, and you’re swimming amongst them, it’s probably not where you want to be,” he said. “I think if you use common sense, you can still swim any month of the year, but you just want to be aware of your surroundings. But every time you get into the ocean, it’s wilderness. It is a somewhat risky environment, but sharks are probably one of the lowest threats compared to boats, and drowning and jet skis.”