History: How much of our islands here are ‘hainted’ by ghosts

BY KAREN GRACE,

BOCA GRANDE HISTORY CENTER

Whether hauntings are real or not, Gasparilla Island and its surroundings have a history of ghost stories. The earliest involve Cayo Pelau, an island to the east of Gasparilla that was once inhabited by Indigenous people and later by pirates. It has been an archaeological site and includes a burial site and a midden from 800 B.C. to 500 B.C., the Glades I period. The early Padilla family who lived on Cayo Costa believed Cayo Pelau was “hainted” (the local word for haunted) and avoided it, as did many of their fishermen descendants.

Cayo Pelau later became the domain of European pirates and even later a place to stash bootleg rum or illegal drugs, as detailed in David Futch’s book, “Historic Stories of Boca Grande.” Another book, “Pirates and Buried Treasure on Florida Islands,” tells the story of a man who was searching for gold on Cayo Pelau. “But the island is cursed – his lunch floats away, and his boat seizes up, forcing him to paddle back to Placida.” Other fishermen tell stories of forces that moved their boats that were not normal wind or tides, and of sudden leaks in boats that disappear when they leave the Cayo Pelau area.

Pirate stories are many on the West Coast of Florida, especially those which feature Jose Gaspar. While it is doubtful that Gaspar actually existed, stories about him continue to be told. Ten years ago, the Beacon told the story of Jose and a “Spanish child princess” named Josepha de Mayorga, and how her ghost still roamed the island’s beaches. Gaspar had tried to seduce the young, captured woman. When she resisted him, at his crew’s urging he cut off her head, which he kept. It is said that he combed her hair and inconsolably stared at her at night. While the story may be fiction, it influenced history. The legend is the basis of the Gasparilla Pirate Festival in Tampa and the source of the naming of Useppa Island, which is said to have been named for Princess Josepha.

The Boca Grande Lighthouse at the island’s south end is also the location of a sad ghost story. According to “American Ghost Stories,” a young daughter of one of the lighthouse keepers died in the dwelling, most likely of diphtheria or whooping cough. The 2015 Beacon article adds that the little girl “loved to play in the upper rooms of the building, where she was surrounded by windows and could watch the sea. Many say that her small face could be seen long into the night, framed against the glass by the bright, revolving light. Those who have been in the lighthouse late in the evening swear you can hear the sound of little running feet, and the rhythmic bounce … bounce of a rubber ball on the floor as her spirit happily plays jacks in the corner of the room she loved so much.”

According to James Ingram’s booklet, “Journey’s End – The History of an Island Home,” the house called Journey’s End was built in 1914 on beachfront property north of the then-existing plat and not connected by a road to the town of Boca Grande. The original owner, Stackhouse, had the house built but left it deserted in less than two years. With no owner, the property became overgrown with underbrush and banana trees. Ingram writes, “In 1921, the area’s worst hurricane rolled the gulf in from the west and over the island. Whatever windows, doors, and furniture that had not been taken from the house by vandals were blown to the mainland. Over a foot of sand covered the floor.” He continues, “Its gaunt and forbidding appearance gave it the name ‘Haunted House.’” Soon a ghost story of a headless woman who walked the beach at night became associated with the house.

When Capt. Frank Davis and his brother Doug talked at History Bytes, they told a story about the ghost they had named George, who lived in the house the Davis family often rented on Gilchrist. George appeared regularly. A bedroom door would open and a bright light would be seen – Doug said it looked like someone had turned on the hall light – then a figure would appear. Once they found footprints on the hall floor in some spilled body powder their sister or mother had used before going to bed. And their dog, Coco, growled at the sound of footsteps coming up the stairs, but no one was ever there.

George was not threatening, and they learned to live with him. In later years, they researched some of the history of the house and found that it was once owned by Seaboard Railroad and had a card room, and that someone who lost at cards later killed himself in an upstairs bedroom, so they surmised that George might be the ghost of the man. Many of the local families also thought the house was haunted, so when Doug first dated his wife, Gail Coleman, she refused to come into the house.

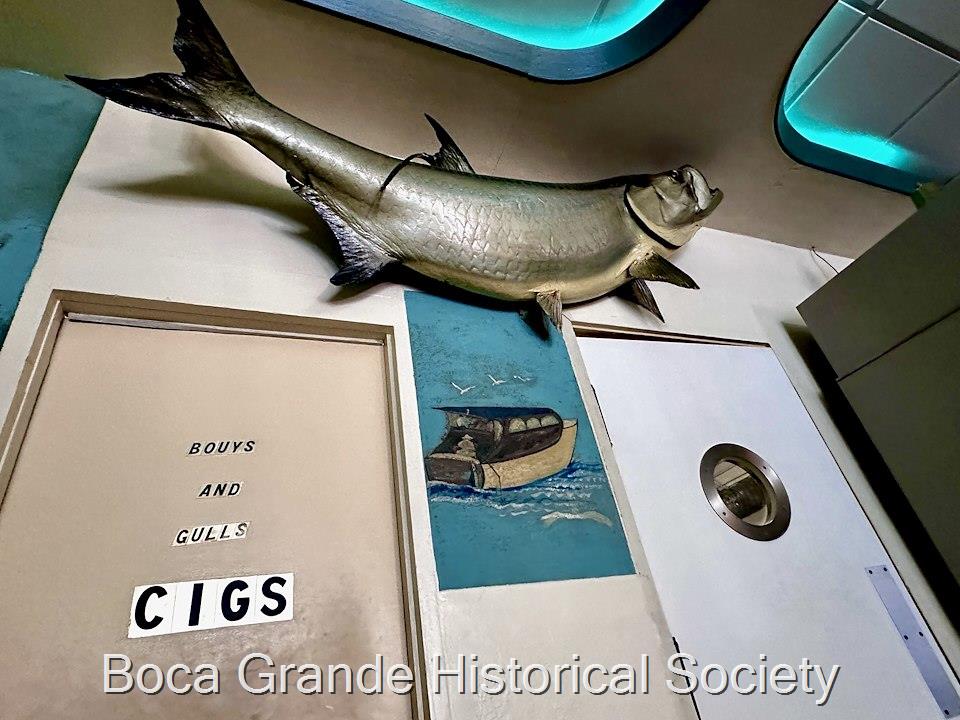

Several of the people who worked at the Temptation encountered Dora, supposedly the ghost of Homer Addison’s wife, who built the Temp. Dora was often seen late at night in the dining room. Rick Montgomery, who grew up in the building while his parents were running the restaurant operation, remembers an evening when his mother, Jean, was trying to open the swinging door between the coffee room and the dining room and felt strong resistance from the other side even though there was no one there. He says they quickly ran into the safety of the kitchen.

Rick also says that he would often hear someone calling his name when alone in the dining room and that the coffee pot would sometimes mysteriously turn off. Paula Johnson, a former bartender, and Jim Grace, a former owner, often saw Dora late in the evenings after customers had left and they were closing. She was like a breeze moving through the dining room, often after a door from the cigarette machine area would unexpectedly and spontaneously open. Like George, Dora never harmed anyone, but the thought of her prevented Rick from wanting to go into the dining room late at night. Early in the Temp’s history, Dora had a piano in the area where the bar and dining room merge, and that seems to be the area she returned to on these nights.

Note: For those interested in local pirate stories, while researching this article I learned that David Futch’s next book, “20th Century Pirates of the Gulf Coast – Tampa to Key West” (working title) will be published in the fall 2026.