IN THE SPOTLIGHT: JoEllen Wilson

Childhood shaped by local waters

For marine scientist JoEllen Wilson, protecting Southwest Florida’s juvenile tarpon habitats isn’t just part of the job. It carries forward a family history rooted in Charlotte Harbor and Boca Grande for decades.

Wilson’s connection to the island stretches back through her mother’s family. Her great-grandparents, Ray and Eileen Maus, owned the Laff-a-Lott – now South Beach Bar & Grille – and her mother, Janet, spent part of her childhood in Boca Grande with her grandmother, Ada Amen. Those early years were filled with shelling, exploring the shoreline and hanging around the old beachfront bar.

Years later, Wilson’s mother returned to the island and secured a small trailer at the north end of Boca Grande. Around that time, she met Wilson’s father – a longtime Englewood resident. They moved around a bit during their early years together before finally settling in Punta Gorda, where Wilson was born and raised.

Her childhood was shaped by the water long before marine science entered the picture. “I was on the boat, starting at five days old,” she said. “My parents fished. That’s what we did every single weekend. We went fishing, so I grew up fishing.”

Fishing wasn’t just recreation; it was part of her family’s rhythm. She assumed she’d follow the same path professionally. “I thought I would be a fishing guide when I got older,” she said, “but I realized that you get up really early in the morning, and most times you don’t get to fish, right? You’re watching other people fish.”

It was that realization in high school – paired with years on the water – that nudged her toward marine science instead. “That’s when I decided to pursue marine science,” she said. Wilson actually started working with the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) when she was in college.

Wilson’s early work with the FWC introduced her to the research side of fishery management. That experience led to volunteer projects with Mote Marine Laboratory during her studies at Florida Gulf Coast University, ultimately opening the door to becoming the Bonefish & Tarpon Trust’s (BTT) first staff member.

“So I worked for BTT as an administrative and research assistant for about three years,” she explained. “At the time, they were outsourcing a lot of the research to universities and graduate students. And so the next project that was coming up was juvenile tarpon habitat use in the Boca Grande area. And I said, ‘That sounds fantastic.’”

She applied to the University of Florida, completed her master’s research on juvenile tarpon habitat use with BTT funding and found herself on the cusp of a career-defining opportunity. “In 2014, when I was finishing up and graduating, BTT was actually hiring scientists on staff,” she said. “And so they hired me back in the position that I’m in now.”

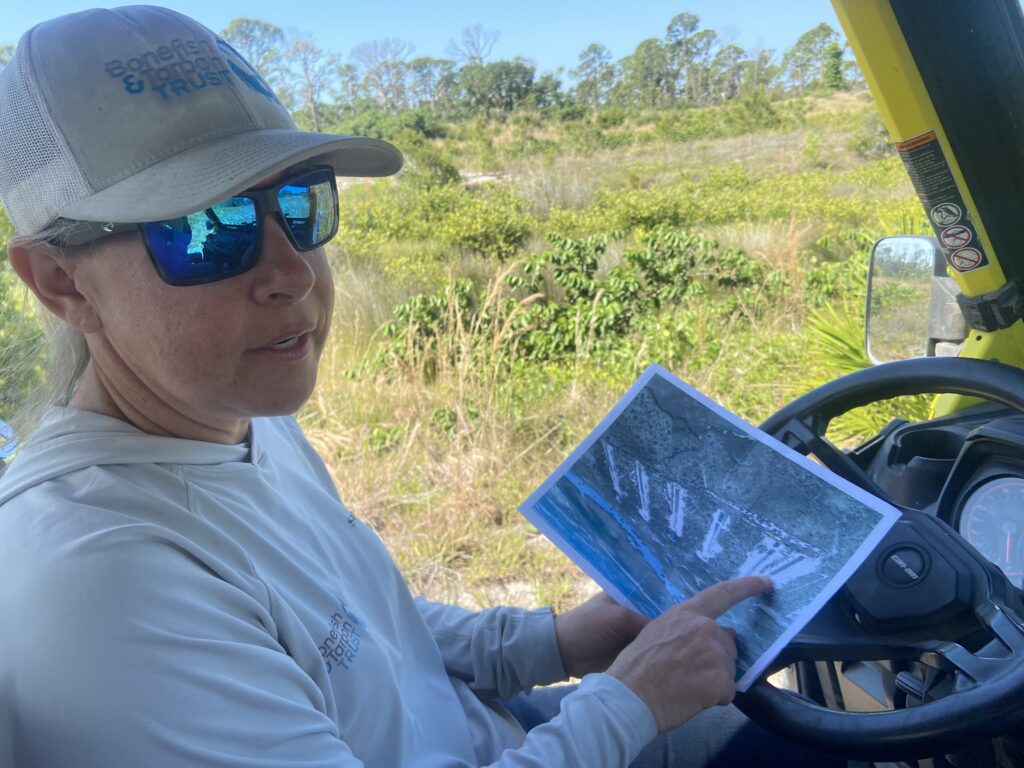

Today, Wilson oversees juvenile tarpon habitat projects from South Carolina through the Florida Keys. Her work involves mapping habitats, restoring degraded nursery wetlands, collaborating with state and local experts and sharing new science with the public.

On Tuesday, she presented in Englewood as part of SUP Englewood’s Coffee & Conservation series, outlining BTT’s expanding restoration research in Charlotte County and in the Boca Grande area, where four potential sites have already completed habitat assessments and conceptual designs. The next phase includes securing grant funding for engineering, final design and permitting – critical steps before restoration can begin.

Wilson sees the work as both ecological and personal. She and her husband follow many of the same generational traditions she grew up with on the harbor. “I have an eight-year-old daughter and five-year-old son, and they’re fishing kids,” she said. “From the time they were born, they were on the boat fishing with us. And so they have this shared passion, and it’s very cool that they get to see the science as well of what we’re doing.”

But even science-driven restoration, she emphasized, begins with community choices: the small decisions to support natural habitats that add up. “I think just taking steps in your own life, and then maybe that will cause a ripple effect out to your direct neighbors, people that you interact with,” she said. “And we can really change how Charlotte County, Charlotte Harbor and Boca Grande residents are able to work a little bit better to protect the resources that we’re all coming here to enjoy.”

Those steps include protecting mangroves on private property, limiting fertilizer use, maintaining natural shorelines where possible and advocating for responsible land and water management. Each of these actions support the same wetlands and tidal creeks juvenile tarpon depend on.

For those who want to make a larger impact, Wilson said habitat restoration often begins with securing the land itself. Much of BTT’s recent focus involves acquiring or protecting parcels where degraded wetlands can be restored to nursery habitat – a strategy that strengthens tarpon and snook populations over generations.

“And so we are just trying to do what we can to improve that,” she said, “and show our kids and show our community that they can do it too.”

Wilson’s work brings together science, family and the waters she grew up on – the same waters her children are learning to fish today. It’s a full-circle story rooted in Charlotte Harbor’s past, yet focused on its future.

To learn more about BTT’s habitat restoration efforts or to support land acquisition for juvenile tarpon nurseries, visit Bonefish & Tarpon Trust at bonefishtarpontrust.org.